And that find has inspired a collaborative community project to unravel the story of their origins and recreate the original object.

The first and only glass of its kind to be found at an archaeological site in Scotland, it is believed the original vessel would have been made in modern-day Syria, Iraq or Egypt during the 12th and 13th centuries, all of which were important centres of Islamic glassmaking.

The fragments are inscribed with part of the Arabic word for ‘eternal’, likely used as one of the 99 names of Allah, which suggests it could be an extract from the Qur’an. Although tiny in size – at 3.1cm x 2.8cm – the two fragments together are smaller than a ping pong ball and give clues to Scotland’s contact with the wider world during the medieval period.

Stefan Sagrott, archaeologist from Historic Environment Scotland (HES), said: “Discovering Islamic glass from the 13th century in a Scottish castle, is an absolutely astounding find. Glass wasn’t commonly used at this time. It was used for stained glass windows in monasteries, cathedrals and some smaller churches and chapels.

“But it’s very rare to find it being used for window glass in castles and tower houses at this time – this happened a couple of hundred years later.

“There wouldn’t be many vessels or objects made from glass either, and if people did have them, they don’t tend to survive today.”

The fragments are back in the spotlight as part of a community project called Eternal Connections. Working with 3D models, creative practitioners and community groups, it used cutting-edge scientific analysis and research data to forge new ways of understanding the contemporary and historic connections between Scotland and Islam.

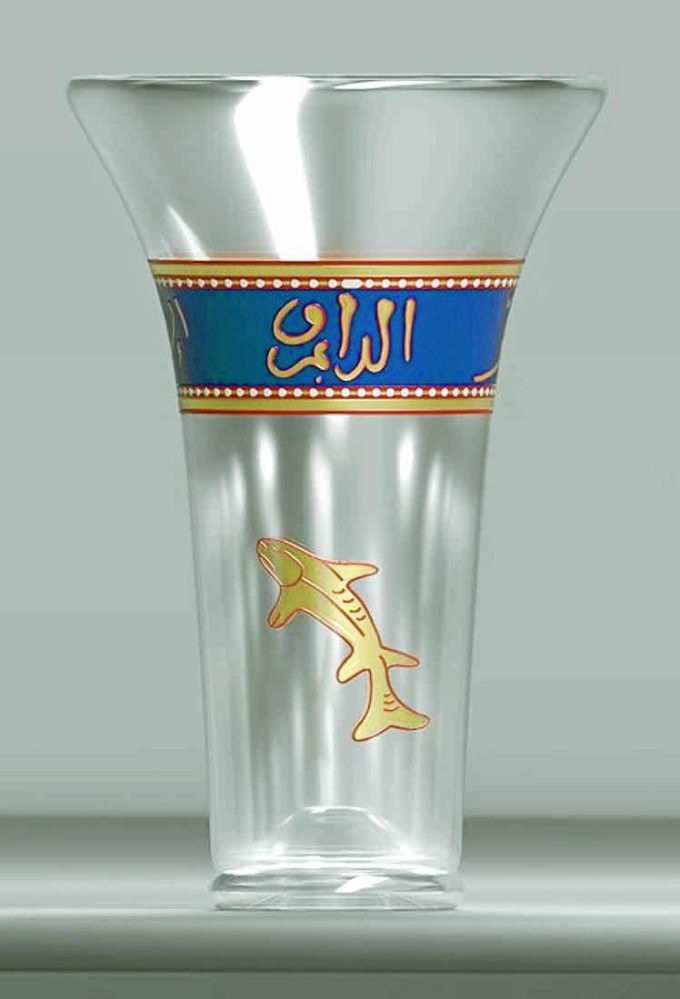

Visual artist Alice Martin researched contemporaneous medieval Islamic glass and worked with experts from HES to analyse the fragments and produce 3D data, then to create a 3D-model digital reconstruction to show what the beaker might have looked like originally.

Alice said: “The fragments are decorated with an Arabic inscription that would have been wrapped around the circumference of the beaker when it was complete.

“Scientific analysis has shown there would once have been red and gold decoration, as well as the blue and white that’s still visible. This type of Islamic glass was thought to be valuable, it’s very precise and delicate.

“From the scientific evidence, research and known history, we thoroughly considered how an Islamic glass drinking beaker ended up in Scotland, and we suspect it may have come to Caerlaverock Castle through trade or could even have been brought back by returning crusaders.

The project worked with community groups, including the Muslim Scouts in Edinburgh and the Glasgow-based AMINA – Muslim Women’s Resource Centre, to provide workshops centred on the story of the Islamic glass.

An interactive online experience has been created using the ThingLink platform to share the project outcomes.